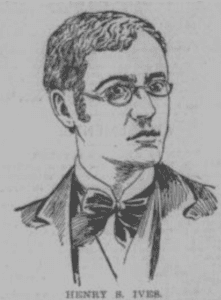

Henry S. Ives, who can be best described as a minor robber baron due to his death at an early age. Ives was born in Litchfield, Connecticut in 1859. His father was a customs house broker and he had two elder sisters, but little else is known of his early life. In personal appearance, he differed widely from his Wall Street rivals who were much older. In his 20s when his notoriety began, he was described as baby-faced, slight of build, bespectacled and short.

At the time of his death, alternate versions of his career appeared in the newspaper obituaries of the day. It would not be unusual, or out of character for a man of Ives’s rapscallion nature to give conflicting accounts of his career to suit his needs in differing cities. Therefore, we report the most verifiable facts below.

In the spring of 1882, Henry Ives, left Connecticut to seek his fortune in New York City. As he had no friends and little education, he was only able to get a place as spittoon cleaner and sweeper. After a year and a half, however, he managed to get a job as a clerk at $10 a week in the office of Charles T. Wing, a broker in the city. Ives quickly learned the details of the railroad business. After he had served a few months in Wing’s office, he astounded his employer one day by proposing a partnership. Mr. Wing declined, and young Ives found new employment with another broker, and soon made his first sensational move by cornering the shares of a small telegraph company. The Board of Governors of the Exchange declared his contracts invalid however and checkmated the young schemer.

Undeterred, his next scheme in early 1885 was to buy up the stock of the Mineral Range Railroad (MRR), a few miles in length, running from Hancock to Calumet in Michigan. Simultaneously though, a Boston syndicate started to build a parallel rail connection to the Mineral Range. This frightened the remaining MRR stockholders so that they sold their stock to Ives and partners at a bargain price. As the Ives party had little money, he used the MRR stock already purchased as collateral for loans and proceeded to acquire full control of the road. From July, 1885 until December, 1886, Ives devoted himself to gutting the MRR treasury so assiduously that he stole some $838,000 to fund his next scheme.

By January, 1886, Ives and partner George Stayner had acquired sufficient funding to start a banking house, Henry S. Ives & Company at 25 Wall Street in New York City. Soon, with the assistance of Christopher Meyer, who was drawn in to that scheme, Ives secured control of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad. Ives used the same methods as in the Mineral Range, buying blocks of stock, using the stock as collateral for new loans and purchasing more of the same stock with the loan proceeds. Ives was now at the height of his glory living the life of a robber baron complete with a yacht, a splendid home and office.

In the summer of 1887, Ives began his plan to put together a transcontinental railroad system with the acquisition of the ailing Baltimore & Ohio railroad. The B&O was to be the Eastern wing of this planned combine. Ives negotiated with the B&O president Robert S. Garrett for an option to purchase a controlling block of stock in the road. With $2,000,000 stolen from the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton he proceeded with the option on the B&O and began to exercise the rights of an owner.

The B&O railroad included the Baltimore & Ohio telegraph system, integral to the operation of the railroad. Ives concocted a deal to sell the telegraph system to the competing Jay Gould controlled Western Union Telegraph for a price reported to between $3,000,000 to $3,500,000. According to accounts, Gould encouraged Ives and in part, may have bankrolled him to make a bid for the B&O knowing that with thin resources Ives would most likely fail and Gould himself could take control of at least the B&O telegraph system to better his investment in Western Union. At this point it seemed that Ives’s scheme was about to fail due to lack of funds to make required stock option payments for the B&O. But as luck would have it, Ives successfully acquired the Terre Haute & Indianapolis Railroad, also known as the “Vandalia Road” and proceeded to steal a further $2,000,000 in furtherance of his plan to control the B&O.

However, in July 1887, it appeared as though Ives had angered a number of very important people. His bankers called his loans, resulting in the Ives & Company collapse. The cause of the called loans was two-fold. B&O management realized the “guaranteed” dividend as part of a $1 million option payment didn’t arrive. Additionally, New York bankers including the influential J.P. Morgan came to the aid of the Pennsylvania Railroad in its quest for access to the St. Louis market.

Ives various schemes finally came to light. He had stolen millions, issued unauthorized stock and bonds and acquired loans collateralized by stocks of his controlled railroads, in furtherance of his scheme and nearly ruined three railroads. It was widely reported that when the Ives & Company firm failed some 10 minutes before the New York Stock Exchange closed on August 11, 1887, the trading floor erupted in unrestrained cheering. He resigned from his firm, Ives & Company the next day.

After resigning from the CH&D the next month in September, 1887, he was sued by the railroad for $7,142,655 in damages and by some forty banks and 160 other creditors for various amounts. His creditors eventually would settle, some years later, taking five cents on the dollar for their claims.

In July of 1888, Ives was arrested and jailed for fourteen months, unable to make $250,000 bail while awaiting trial. During his time in Ludlow Street jail in New York City, he reportedly paid $10,000 for little privileges which were sometimes afforded to those prisoners that had cash to spare. Ives was freed in March, 1890 on a reduced bond of $5,000. Afterwards, when the Fassett Committee, impaneled to review allegations of political corruption in New York, began looking into the inequitable conditions that existed at the jail, Ives was called as a witness.

In November 1892 Ives married Miss Helen Gertrude of Lockport, NY. She was formerly a member of the Bostonians Opera Company and at the time Ives stated that had been engaged to her for some five years. Ives and his new wife made their home at 6 West 56th Street in New York City, a property that had been leased by him for several years.

After being released from jail, Ives soon returned to his old habit of acquiring railroads, including the Cleveland, Akron & Columbus railroad in 1893 along with an interest in the Ohio Southern railroad, but this was cut short by illness. On April 17, 1894 at the age of 35, Ives would die of tuberculosis at Beatty Bungalow, a rented home situated in the foothills of the Blue Ridge mountains just outside of Asheville, North Carolina and within view of George W. Vanderbilt’s estate. There was some speculation at the time that his illness was contracted during his time imprisoned in New York. In an abundance of caution, in part due to his reputation, his family had Ives’s remains interned at a private ceremony in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.